By David DesRoches

A Special Reporting Project from Connecticut Public Radio

May 24, 2019

The Hospital

As she sat with her newborn in the hospital bed after a long and painful labor, an exhausted Corrine Walters held her son close, rocking him in her tired arms. Her first child. She smiled at him.

“Hi Jackson, you’re here, finally!” Corinne remembered saying. “I’m your mom!”

It was July 1, 2011, and that inimitable feeling of creating a life overwhelmed her and her husband, Ryan. The pregnancy had gone perfectly. Newly married, the couple had recently graduated college, gotten jobs, and bought a condominium in Connecticut. They had wanted to wait a year before trying for kids, and by the time they were ready, she got pregnant.

Photo courtesy of the Walters Family

“Everything was going great,” Corinne said. “He was the first grandchild so the whole family was super excited.”

Friends had told her about that special moment when your child hears your voice and connects to you. There’s even evidence that a baby in the womb can already identify the mother’s voice. Corinne couldn’t wait to say hello.

But something unexpected happened. Jackson wouldn’t respond to her voice. He instead stared at the bright fluorescent lights above the bed. He appeared captivated by them.

“I knew something was going on,” she said. But she questioned herself.

“Moms are very hypervigilant when it comes to their kids and I think that was my first ‘mom moment’,” she said. “Like, what’s wrong with him? It was just something that I questioned for one second and then it went away.”

When Jackson failed the initial hearing screening at the hospital, nurses and friends told Corinne it’s common. It’s just the amniotic fluid in his ears from the labor, it will pass. She went back for another test a week later, and he failed that one, too. A third test was scheduled.

“In that time, of course I started doing crazy stuff, like smashing kitchen pans together and screaming real quick to see if he would get startled, and he wasn’t,” she said. “Then I started to get a little nervous.”

Jackson had to be asleep for the third test, called an auditory brainstem response, which shows whether the inner ear, or cochlea, is working. It also checks the brain pathways for hearing. An audiologist placed electrodes onto her son’s tiny head while he slept. A machine sent signals through the electrodes and into Jackson’s brain, measuring the response.

“I didn’t fully understand the whole test, so I was kind of praying he would sleep the whole time,” she said. The machine was connected to a computer that she watched as they tested her son. The monitor remained blank.

“I can still picture the screen,” she said. “They were getting nothing… I didn’t see any of the movement the whole time. When she told me that that’s what they had been looking for over the past 45 minutes, I just lost it, I started crying.”

I can still picture the screen … they were getting nothing.”

They told her Jackson was profoundly deaf, unable to hear any sound.

“Like, sign language deaf?” Corinne remembered asking, admitting now that she didn’t know there was a spectrum of hearing abilities.

“I didn’t know anything about cochlear implants or that deaf people could learn to speak,” she said.

Within minutes, a hospital worker handed her two pamphlets about her options and that was it.

“And we were sent home,” she said. Other families were waiting for their tests, and there wasn’t any time for consultation, or consolation.

Now she and her husband had to make a choice — and they had to choose quickly. How would Jackson communicate? Should they teach him sign language? Or should they teach him to speak? Both? Every moment of delay risked stifling his brain development.

Questions raced through her head. What does all this mean? What’s next? The questions multiplied as her family learned more. As they sought help, it quickly became apparent that there were deep divisions among the experts. Precious time began to slip away with every contradictory thing she was told.

They needed time to think. But Jackson needed language immediately.

Photo: Cloe Poisson for Connecticut Public Radio

The Debate

The question of whether something is “wrong” with someone because he is deaf has ancient and endless roots. Alexander Graham Bell was a well-known anti-sign language activist. Bell’s wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard, was deaf, and he advocated what’s now known as the oral approach. He wanted deaf people to be fully integrated into society, and believed spoken language and lip reading was the only path.

For advocates of the spoken word, the debate over deafness and whether it’s a disability that should be cured or a reality that should be celebrated has been settled. Advances in surgery techniques and technology have given many people access to sound — people who, only 50 years ago, would have remained in a silent world their entire lives. Every year technology improves and access expands.

But for many in the signing Deaf* community, the debate over the nature of deafness is not a fair one. That’s because one side is reinforced by a supermajority that has, for millennia, used spoken language to not only communicate, but to convey reality, meaning, ideas, abstract thought, and even humor. Most importantly, this supermajority is responsible for developing and implementing the English and oral-language based systems through which all learning happens in the U.S.

* In 1972, linguist James Woodward proposed distinguishing between deafness as an audiological condition with a lower case “d” (deaf), and Deaf culture, with an uppercase “D” (Deaf). We have chosen to use that convention in this story.

For people who hear, the definition of deafness is often medical in nature — a disability that should be cured. For Deaf people, the definition of deafness is personal, varied, complex, nuanced, passionate, and sometimes contradictory.

For people who hear, the definition of deafness is often medical in nature — a disability that should be cured. For Deaf people, the definition of deafness is personal, varied, complex, nuanced, passionate and sometimes contradictory.

Jeff Bravin understands that his deafness is often perceived as disabling, but for him, it’s a disability that does not impact his sense of normalcy. Bravin is the executive director of the American School for the Deaf in West Hartford, the oldest permanent school for the deaf in the United States.

“You would never know I was a deaf person if we emailed back and forth,” said Bravin, speaking through a sign language interpreter. “I function as any normal person.”

This idea of normalcy — that a person can be both deaf and normal — is one that parents of newborn deaf babies often struggle with. As technology advances, however, new opportunities are presenting themselves. Some devices enable the deaf to hear better, and others help them to interact with the hearing world without speaking. Voice-to-text software and TTY telephones are two examples of the latter.

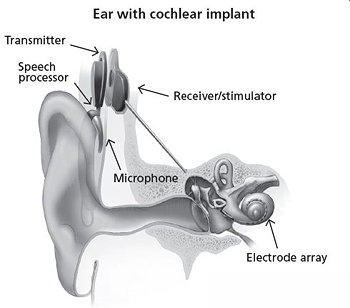

However, the place where technology intersects with language is where debate begins to heat up. On one side are the speech advocates, known as oralists. They push for spoken language only and technological hearing interventions, like cochlear implants, which are devices that are surgically implanted behind the ear and convert sound waves into electrical impulses to give a deaf person a modified sense of sound.

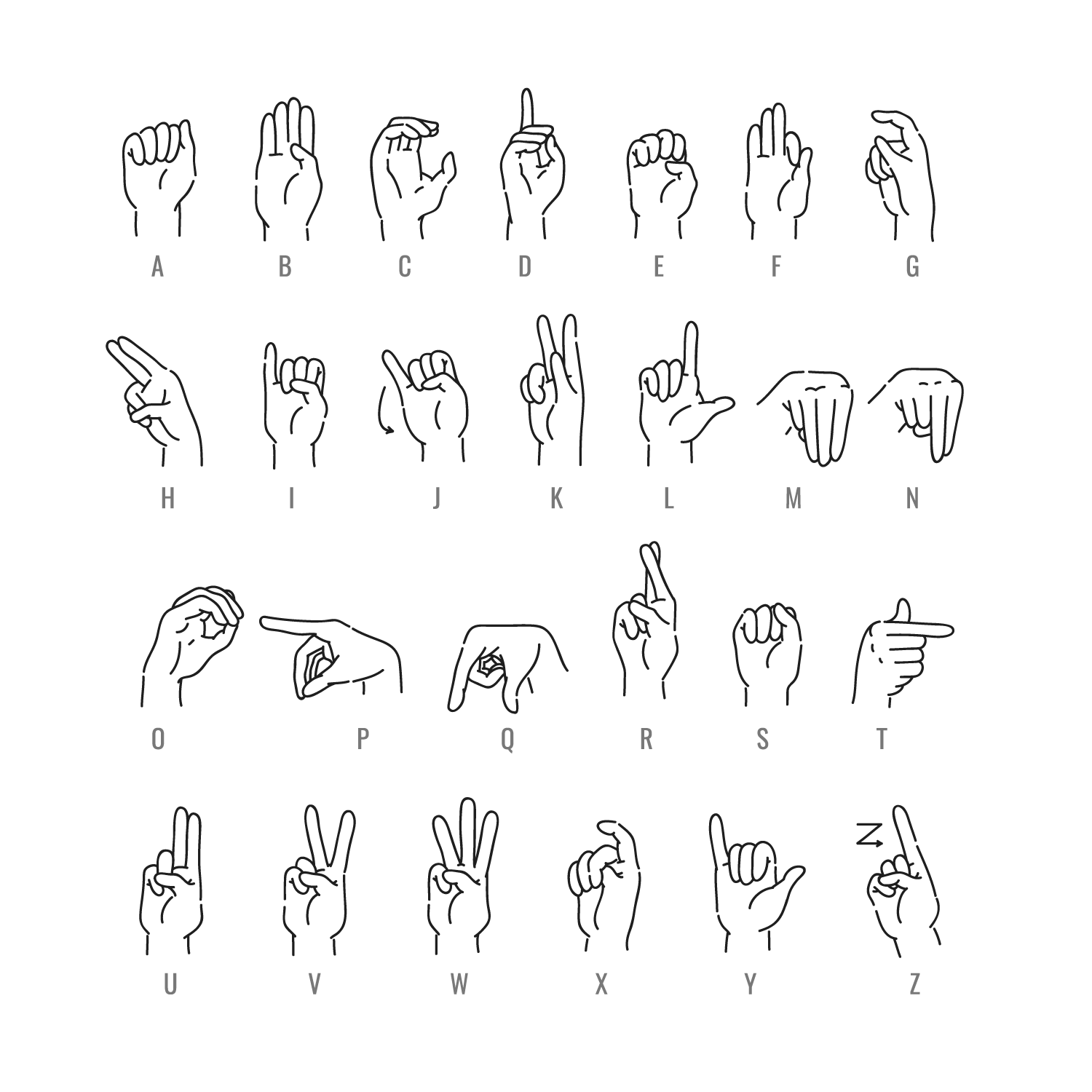

On the other side are the American Sign Language (ASL) advocates, who often take a bilingual approach. This can take the form of signing and written English, or signing and spoken/written English. ASL proponents view inner-ear technology as a communication supplement, instead of a primary input source.

The book, Made to Hear, by Laura Mauldin, describes the conflict this way: cochlear “implantation has the central goal of controlling the development of the deaf child’s brain by boosting synapses for spoken language and inhibiting those for sign language, placing the politics of neuroscience front and center.”

It’s estimated that about 80 percent of children born deaf in the developed world are implanted. What effect this has had on ASL is unclear — that’s because nobody tracks the number of people who use ASL. The U.S. Census Bureau only collects data on oral languages, and considers signing a form of English.

The lack of data further confuses new parents who are asked to absorb conflicting information while trying to quickly make a language decision for their deaf infant.

Photo: David DesRoches, Connecticut Public Radio

“If you choose sign language, then you need to get really fluent in sign language very fast,” said Elizabeth Cole, who at the time of her interview was director of CREC Soundbridge, one of two oral-only programs for deaf or hard-of-hearing infants and toddlers in Connecticut. “A visual language is very different.”

Cole pointed out that any child — deaf or hearing — needs to be immersed in a language for proper brain development. Since 90 to 95 percent of deaf children are born to hearing parents, who cannot sign, going the ASL route can prove daunting, she said.

Bravin, from the American School for the Deaf, takes a difference approach. He said the focus should be on language accessibility for the child. The oral-only approach assumes that all children will be able to speak and hear just fine with the right mix of technology and education, however that’s not always the case.

Photo: David DesRoches, Connecticut Public Radio

“Every parent wants one thing — they want their child to be normal,” Bravin said. “The parents will do whatever they can to make their child normal, to the point where they realize there’s nothing more that can be done.”

Oral programs are “riding on the idea that they can make the parents believe that their child’s going to be normal,” Bravin continued. “That’s their belief, and that’s OK… My belief is that every child here is normal because they have full language access right here. And I can prove it. I’m living proof.”

Both Bravin and Cole said they respect a parent’s right to choose which communication mode fits their family. But when it comes to which program they think is best, their allegiances are clear — as is their mutual skepticism of the other’s approach.

While there’s no data on how long it takes the average person to become fluent in ASL, the U.S. state department’s Foreign Service Institute estimates that it can take up to 2,200 hours just to become somewhat proficient with some foreign languages. At 20 hours of studying per week, that’s over two years. For parents who have recently learned their baby is deaf, that can be a daunting proposition.

Enlarge

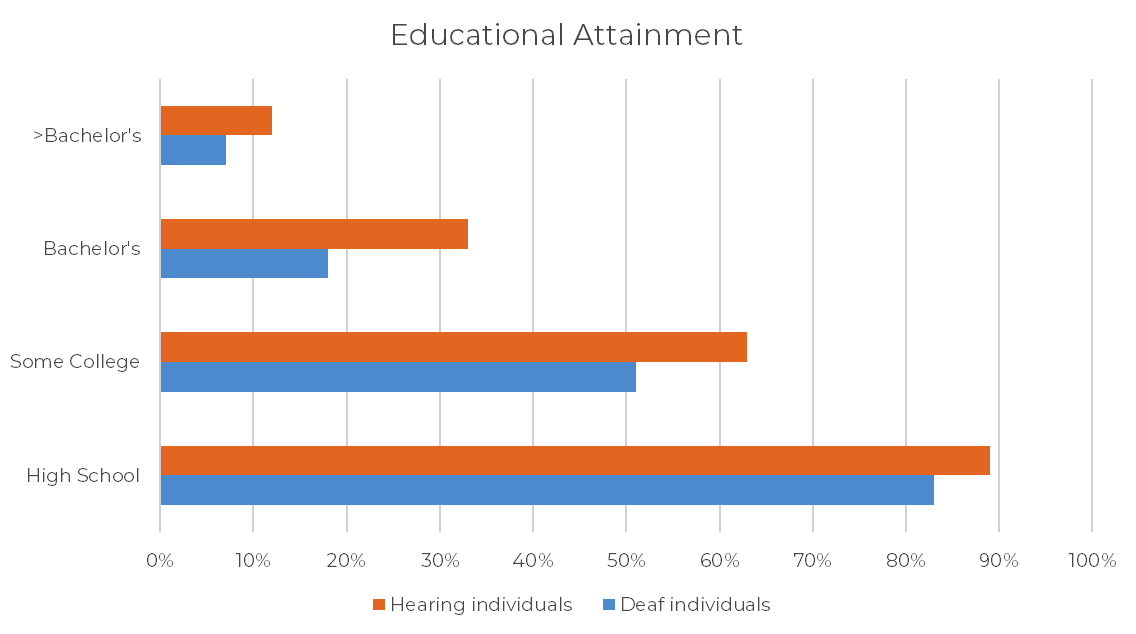

Source: Gallaudet Research Institute, 2013

Each side has peer-reviewed research, and each side has strong criticism of the other’s data. When it’s time to make a choice, new parents have only days to sift through conflicting research and choose how they want their child to communicate.

Should they live in their child’s world and learn to sign, or should their child live in their world and learn to speak? Should their child be fixed, or is their child already normal?

Photo: Cloe Poisson for Connecticut Public Radio

The Decision

Corinne and Ryan Walters had to learn about deafness, and act, fast. They learned about cochlear implants and hearing aids. They learned about ASL and Deaf culture.

But when they reached out to the different service providers, they got conflicting advice. Oralists told them not to sign with Jackson. “He’ll never talk,” they said. ASL advocates told them to sign with Jackson as much as possible so he would have full access to language.

“It was really confusing,” Corinne said. “And the scary part is, everyone you speak to is like, ‘you need to do this now’.”

They saw a cochlear implant mapping session, which is a process that involves sending various sounds at different volumes through the implant to see which tones a child can hear, and which ones need adjusting. They also met other parents and kids with implants.

“They weren’t all poster children, some of them were not speaking well,” Corinne said. “You have these directors of these schools trying to sell you their school, and they’re going to tell you why this is good and this is bad. But talking to the parents and seeing the kids who had already gone through it all definitely helped me the most.”

A decision was made. They wanted Jackson to get cochlear implants and learn to speak. They enrolled him at CREC Soundbridge’s Birth-to-Three program. But something irked Jackson’s parents. Soundbridge told them not to sign with Jackson, that it would interfere with his speech development. That meant they wouldn’t be able to communicate with their son for an entire year while waiting for the implants, because the Food and Drug Administration won’t allow implants earlier.

“In my head, I’m like, ‘I have to wait a year with this kid having no language,’ and that was stressful to me,” Corinne said. So she chose to ignore Soundbridge’s recommendation and signed with her son. She took community college courses and began building her ASL vocabulary so she could teach it to Jackson. Contrary to what she was told, Jackson’s signing didn’t hamper his talking.

“I’m glad I still signed, even though they said not to,” she said. “He knows enough sign language where, without his ears on, we can have a conversation.”

I’m still glad I signed, even though they said not to,” she said. “He knows enough sign language where without his ears on, we can have a conversation.”

— Corinne Walters

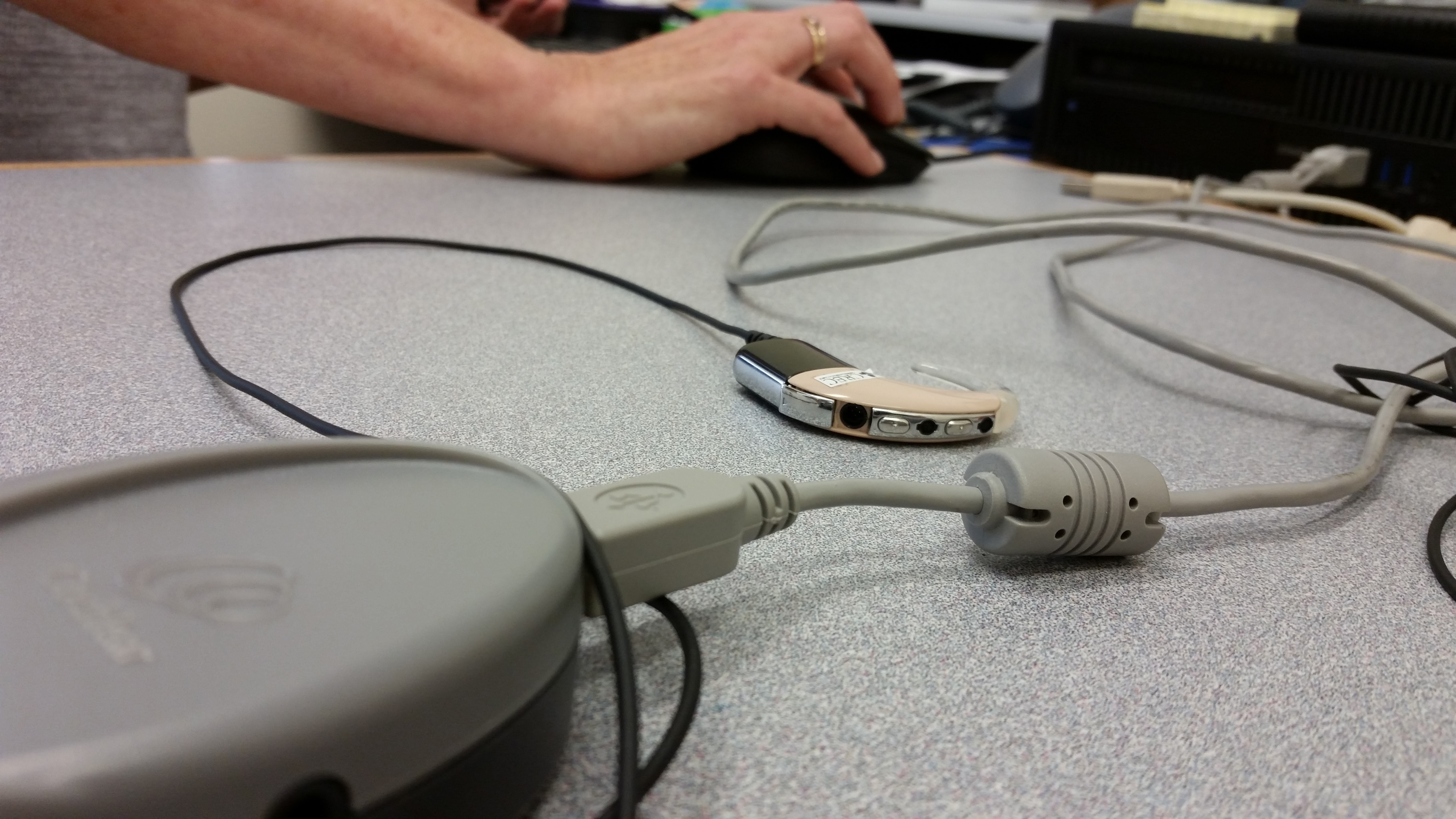

The “ears” are the part of the device that’s worn outside the actual ear, and can be taken off.

Jackson’s younger brother, Chase, was also born deaf. Genetic testing showed that both Ryan and Corinne carry a mutated gene called connexin 26. This gene is responsible for about 20 percent of all hearing loss, according to the California Ear Institute.

Courtesy of the Walters family

But they took a different language path with Chase. Corinne began signing with him just as she had with Jackson, but stopped with Chase soon after he was implanted. Chase wasn’t developing speech as quickly as his brother had, and Corinne succumbed to the fear that she’d heard from the oralists — if you sign with him, he’ll never speak.

“I didn’t want what they tell you will happen, to happen,” she said.

Istockphoto

When she thinks about how her sons developed differently, she can’t help but consider whether sign language played a role. From the perspective of the ASL advocates, it’s clear — signing with Jackson helped him learn to talk. They’d also say that her younger son was slow to develop speech because Corinne stopped signing with him. However, oral advocates would say the opposite — that Chase was delayed precisely because Corinne signed with him at all. But Corinne is somewhere in the middle.

“It’s kind of ironic that I didn’t sign with Chase and his speech was so delayed,” she said. “And I did with Jackson and he has perfectly clear speech.”

Life in the Walters’ home is much like any other home, aside from some small modifications. It’s tough to call the kids for dinner, so the parents flick lights or pound walls to alert the presence of food. Jackson and Chase can’t hear fire alarms, so they have devices that vibrate their beds in case of an emergency.

As for their “ears”, it’s a perpetually expensive process of battery changes, processor upgrades, and audiologist appointments. But for Corinne, a significant and complex struggle is balancing the reality of her children’s deafness with the desire to keep them integrated in the hearing world.

“Yes, they’re deaf and we want them to know that and we want them to have Deaf culture knowledge and we want them to know a little sign language just in case, God forbid, something ever happened,” Corinne said. “But they’re hearing and they’re living in a hearing world just fine.”

She also knows she’s lucky.

The cost of cochlear implants can run into six figures. Many insurance plans will cover most of these costs, but not all. For the uninsured, implants can be nearly impossible to obtain, though there are some programs that offer financial assistance. Children on Medicaid are eligible for implants, but the process is often lengthy and cumbersome.

Photo: Cloe Poisson for Connecticut Public Radio

Living Between Worlds

Choosing between ASL or spoken language is often more controversial among researchers than it is among parents. Of the dozens of deaf children and adults interviewed for this story, nearly all of them know at least some sign language. Some communicate with sign-only, but even the children whose parents are strongly against ASL used some signs. Most parents seem to choose what works for their family.

“We call it the Posner code,” said Rachel Posner, a professor at Naugatuck Community College and a mother of two deaf children. Her daughter, Faith, has a hearing aid, as does her son, Henry. They can both speak and sign.

We call it the Posner code,” says Rachel Posner. … Her daughter, Faith, has a hearing aid, and her son, Henry, has a cochlear implant. They can boke speak and sign.

“We don’t follow any model,” she said. “I know that I’d be crucified — maybe some people would be like, ‘Great, that’s just fabulous.’ Other people would be like, ‘F you, you’re ruining the culture.’ I’m not here to do anything to anybody, but to make my kids the best they can be.”

Rachel and her husband, Mick, are also deaf and ASL/English bilingual. Mick grew up on Long Island and learned to sign. Rachel is a Connecticut native, and grew up in a family that wanted her to speak.

Above: Mick and Rachel Posner talk about straddling the hearing and deaf worlds. Both Mick and Rachel were born deaf. They met in college. Editor’s Note: In this video, subtitles are interpretations of Mick Posner’s signing, while they’re used to caption Rachel Posner’s spoken words.

“In theory, I am more deaf than my husband, but because I had speech training growing up, I speak better than him,” she said.

Rachel’s parents didn’t know she was deaf until she was three. When she was a child, she used a hearing aid to help her, but it was always a challenge.

“I watched TV without closed captions so I had to train myself to hear,” she said. . She also developed a domineering personality, she said, so she could control the conversation. Her daughter now does the same thing.

“That was how I survived,” Rachel said. “If somebody talked about random things, I’d get lost.”

Rachel often found herself doing things out of a sense of survival. As she became a teenager, that survival instinct became more complicated, and her struggles more personal.

“I hated high school, because everybody would be laughing and I would laugh along with them, but I wouldn’t know what they were laughing at,” she said.

For the most part, Rachel was content living in the hearing world, even if it took constant and often painstaking effort. Eventually she was confronted by another world — one that had remained nothing more than a curiosity for most of her young life.

She had taken a job at a roller skating rink running the food counter. The music was always loud, so her lip-reading abilities came in handy. She was in the eleventh grade, working her usual shift when a customer took her by surprise. Rachel was wearing a hearing aid, and a young woman in line noticed it and immediately began signing.

“All I could see was her hands flying, and I was like, ‘Whoa, whoa, I don’t know any sign’,” Rachel said. “But that made me feel bad, because it woke up a part of me, like, ‘Wait a minute, I should know sign’.”

They exchanged addresses and kept in touch. She later invited Rachel to prom at the American School for the Deaf, where everyone signs. Even though Rachel couldn’t sign, she decided to go. She had to take a note pad with her so she could interact.

“When I got to the prom I felt so terrible that in order to communicate, people had to write,” she said. “I realized, ‘you know what? This isn’t me anymore’.”

Her senior year of high school, she left her friends at public school and enrolled at the American School for the Deaf so she could learn ASL. But it wasn’t easy.

“I decided to live there in the dorm and throw myself into Deaf culture,” she said. “It was tough, because I wasn’t fully accepted in the hearing culture, but I also wasn’t fully accepted by the Deaf culture. I was too oral, I was too hearing.”

She later went to Gallaudet University, known as the world’s first college for the deaf, and the only college in the world where all programs are designed for deaf and hard of hearing people. That’s where she met her husband, Mick.

The couple has used their diverse background to craft what they call the “Posner code,” which is using sign and spoken languages as needed, and sometimes at the same time.

“It’s what works for our family,” Rachel said.

They wanted their children to have a good ASL foundation, but they also wanted them to talk. So they switched back and forth between the American School for the Deaf — the only school in Connecticut that offers ASL — and CREC Soundbridge, the oral-only school for deaf and hard of hearing students.

Rachel wants her children to have exposure to both worlds, and both cultures. At school, they get hearing culture. At certain events for the signing deaf, they get Deaf culture. At home, they get both.

“You still need that balance,” Rachel said. “My kids have that balance.”

Below, The Posners – Henry, 7, Mick, Rachel and Faith, 10, who are hearing impaired, use a combination of spoken language and American Sign Language to converse while having lunch at their Plainville home. Rachel and Mick decided to raise the children using spoken language and American Sign Language, as opposed to cochlear implants, to teach them to communicate. Photos by Cloe Poisson for Connecticut Public Radio

Her daughter, Faith, has struggled with that balance. One time she was in a store signing with her mom and she saw a classmate from school and became embarrassed.

“I asked Faith, I said, ‘What’s the problem?’” Rachel said. “And she said, ‘I have my hearing life at school and my deaf life at home, and I don’t like to mix them both.”

It upset Rachel. She wanted her daughter to take pride in her deafness, and own it. Rachel later called Faith’s teacher-of-the-deaf — the person assigned to help deaf or hard of hearing students in public schools.

Rachel asked the teacher if Faith could lead the class in a sign language lesson. Faith’s birthday was coming up and the whole class had been invited to her party, along with people from the Deaf community. Rachel wanted the class to be familiar with the language, and the culture.

“We didn’t want a divide,” Rachel said. The teacher agreed, and Faith taught her class some ASL. It wasn’t long before the text messages started rolling in from other parents to Rachel’s cell phone, excited that their kids were learning to sign. “I showed her the messages and was like, ‘See? It’s not such a stigma’.”

The birthday came along, and everyone showed up.

“When it was time to sing happy birthday,” Faith said, her eyes bright, “they started SIGNing!”

“My heart melted,” Rachel said. “A little bit of awareness, and a little bit of acceptance, and little bit of communication, goes a long way.”

For Faith, that’s when the balance started to make sense.

“It was like the best day ever,” Faith said. “They were all just signing awesomely. It was just so weird, because like a week before I taught them how to sign. And they must have been practicing at home or something, because they were, like, pros.”

Photo: Cloe Poisson for Connecticut Public Radio

The Politics of Language

“If you teach your child to sign, she’ll never learn to speak.”

It’s a statement that parents have heard for centuries. For equally as long, there has been little evidence to support this idea, aside from the occasional anecdote. That is, until fairly recently.

In 2017, a study called, “Early Sign Language Exposure and Cochlear Implantation Benefits,” also known as the Geers study, after lead author and psychologist Ann Geers, provided fuel for this popular oralist claim. Written by five researchers from various universities and medical schools, the article presents data to suggest that children who are exposed to any form of sign language aren’t able to recognize speech as well as children who had no sign language.

Oralists, such as Soundbridge’s Elizabeth Cole, point to this article possibly ending this debate.

“You can find research in this field to support any point of view,” Cole said. “A lot of it is not worthy of consideration, to be polite.”

“This is solid,” she said, laying her hands on top of a computer-printed version of the Geers study.

In an interview, Geers, a developmental psychologist who’s studied deaf children for over 50 years, said she’s convinced that early signing exposure leads to delayed speech for children with hearing parents.

“It would be delightful if these kids could have two language systems that were equally well-developed,” Geers said. “I wish that were true. But I’ve been studying this for more years than a lot of people have lived, and I just haven’t seen it happen.”

Some, however, claimed the study has serious methodological flaws, and its findings could mislead parents and hamper their ability to make informed decisions about language choice.

“It’s really scientifically unfounded,” said Marie Coppola, a psychology and language professor at the University of Connecticut, referring to the Geers study. One of Coppola’s concerns centers around the authors’ definition of sign language — they lumped together kids who did any sort of sign into one group. It didn’t matter if it was ASL, baby signs, or even single signs.

“What’s problematic about that,” Coppola said, “is they make recommendations about sign language, or signing. And this is why parents find some of these reports confusing.”

In defense of her work, Geers said that even when she separated children who received ASL-only, the findings were the same. However, she admitted her team didn’t track how much ASL each child was getting, or for how long they were getting it.

The “specific sign language they are trying to learn is not as important as the fact that they are using sign with their baby and the outcomes are not as good as for children whose parents focus on developing spoken language following [cochlear] implantation,” Geers wrote in an email.

The question of objectivity often comes up in discussions with researchers from both sides of the debate. In the case of the Geers study, three of the five authors received funding from Advanced Bionics, which develops and sells cochlear implants. In Coppola’s case, both her parents are deaf and she grew up signing with them.

The question of objectivity often comes up in discussions with researchers from both sides of the debate.

Researchers sensitive to Deaf culture are often the only ones the Deaf community trusts to research individuals within that community. This could, oralists have argued, lead to research by those who might seek findings that support the culture. Coppola said she understands that concern, but takes issue with the framing.

“It’s difficult to be in this position as somebody who is part of the Deaf community and values sign language,” Coppola said. “That’s seen as somehow a bias, whereas the people advocating speech only — that’s just normal, that’s how it is.”

Above: Kim and John Silva reflect on their experiences as a deaf couple. Both were born deaf. They recall moments of living in a hearing world. Editor’s Note: Sometimes when people sign and speak simultaneously, the languages do not align. The subtitles are interpretations of the signing, not the speaking.

Diane Lilo-Martin, a linguistics professor at UConn, said a key point of separation between researchers is the very nature of language itself.

“To look at the two languages… as equals” is one way to see it, Lilo-Martin said, referring to ASL and English, “as opposed to only seeing the sign language as a tool for the spoken language.”

Many Deaf people are wary of research done by those in the medical community who view deafness as something to be cured. This fear is rooted in a history of unethical practices involving eugenics and genetic research to “cure” deafness, which would essentially eradicate Deaf culture, according to a paper published in the American Journal of Public Health.

“Few health researchers understand the cultural values held by the Deaf community or even know ASL,” the authors wrote. “The lack of linguistic and cultural concordance places the population at high risk for poor research engagement…”

Researchers such as Coppola point out that the most academically successful deaf people are those who grow up signing in Deaf families.

“Maybe we can learn — take that as a starting point to generate hypotheses,” Coppola said. “And that’s the approach that [we’ve] taken in our work.”

However, the research is conflicting. Some studies support Coppola’s stance.

“Findings suggested that students highly proficient in ASL outperformed their less proficient peers in nationally standardized measures of reading comprehension, English language use, and mathematics,” reads a study from the Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education.

But a separate study from another peer-reviewed journal offers a different take.

“A recent comprehensive review of the literature on reading skills in students with [cochlear implants] concluded that children with implants frequently read better than deaf peers,” reads a study from Ear and Hearing.

It’s further complicated by an assortment of semantic and philosophical disagreements. Signing means one thing to one camp, and another thing to the other. Hearing aids and implants are assistive technology to some, medical devices to access language to others. Some say reading and writing English is fine, others say spoken language is true mastery. This is only part of what parents have to navigate once they learn their infant is deaf, and with no delay.

No matter what parents choose — spoken language, ASL, or a combination — both Cole from Soundbridge and Bravin from the American School for the Deaf say the key is parent involvement.

No matter what parents choose — spoke language, ASL, or a combination — both Cole from Soundbridge and Bravin from the American School for the Deaf say the key is parent involvement.

“I’ve seen children struggling in school, but because the parents are so involved and so invested the child does well,” Bravin said. “The bottom line is how much the parents are involved in the children’s upbringing and educational career.”

Photo: Cloe Poisson for Connecticut Public Radio

On Data … and the Lack of It

Only about 70 kids are diagnosed with a hearing loss annually in Connecticut, according to the state Department of Public Health. This number doesn’t account for the many kids who slip through the cracks, a problem the department has been aware of for years. Just under 38,000 babies are born in the state each year.

Some children develop deafness later in life. Fewer than one in 1,000 people become deaf before their 18th birthday, and only about two to four people per 1,000 are functionally deaf, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

When it comes to educational outcomes, there’s a paucity of data on students who are deaf or hard of hearing. Connecticut only tracks deaf students in special education programs; that is, many deaf students receive additional supports through something called a 504 plan, but those students aren’t tracked.

For the deaf students who are tracked, their academic performance is among the worst of any disability. State data shows that between 2016 and 2018, less than a quarter of these students were proficient in math and English.

Enlarge

SOURCE: National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes

Across the country, outcomes remain consistently poor. Some speculate that it’s because of a lack of school resources — it could cost more than $1 million to educate and provide various adaptive services to a child who’s deafness is identified before three years old, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Researchers have pointed out that a high percentage of deaf high school students don’t graduate on time, and have low test scores in reading, writing, and math. But the medical history of these children isn’t public information, so it’s difficult to know what language modality the students are pursuing, and whether they have cochlear implants or hearing aides, and what kind of supports they’re actually receiving in the classroom.

There’s even less data when it comes to ASL. While Gallaudet University conducts surveys to estimate how many families use ASL at home, it’s still unclear how many people use ASL as a first language in the United States.

“I’ve never seen good stats on this,” said Matt Hall, a psychology professor at the University of Massachusetts.

The last time there was an effort to determine how many people use ASL as a first language was in 1996. That estimate placed the number between 500,000 and 2 million in the U.S.

Even in places where data collection could be beneficial, it’s not happening. Even though most students at the American School for the Deaf learn ASL, the school actually doesn’t track how many of its students are learning ASL — even though the school publicly advocates its value alongside the knowledge of English, and even though many in the Deaf community fear ASL as a primary language is slowly dying.

Even in places where data collection could be beneficial, it’s not happening.

“We don’t track that, we have no reason to track that,” said Bravin, ASD’s director, through an interpreter. “That’s a good question for the state.”

The main nationwide method that’s used to determine how many languages in the U.S. are used, the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, does not include ASL. All the listed languages are spoken. In fact, the Bureau actually counts ASL users as English speakers, and points to the Voting Rights Act as justification.

“The enforcement of the Voting Rights Act is focused on non-English languages that are spoken by members of racial minority groups,” the Bureau states on its website. “The law does not address or provide for sign languages used by hearing disabled population.”

That, advocates of the deaf would argue, is an example of “oralism” — the idea that languages can only be spoken and heard, and never signed and seen — and how that mentality colors research and data-gathering.

Dr. Laura Ann Petitto, a cognitive neuroscientist at Gallaudet University, said this is especially problematic in the United States, where monolingualism is the norm.

“Here there’s almost a double whammy,” Petitto said. “You have this resistance to bilingualism, and this extreme focus on one language, and this combination is not optimal…

Petitto pointed out that the natural language of a deaf person is visual, and if their heightened visual-processing power isn’t nurtured, she said, then it’s like “holding back a rocket with a hundred horses.”

“If you have a brain that’s set for spectacular visual processing,” Petitto said, “and I say, ‘No, I’m not gonna give you that. You are gonna remember sound. This sound, that sound. And I’m gonna drill you.’ You’re tying the roots of a tree that could have been magnificent.”

She said it’s hard to imagine a hearing-child growing up in the U.S. and not learning English, because it seems natural. For a deaf child, that expectation should be the same, except the language should be ASL. However, because many see deafness as a medical condition, Petitto said ASL is often seen as an impediment to learning English, and not as a natural first language.

Photo: David DesRoches, Connecticut Public Radio

When Language Begins to Suffer

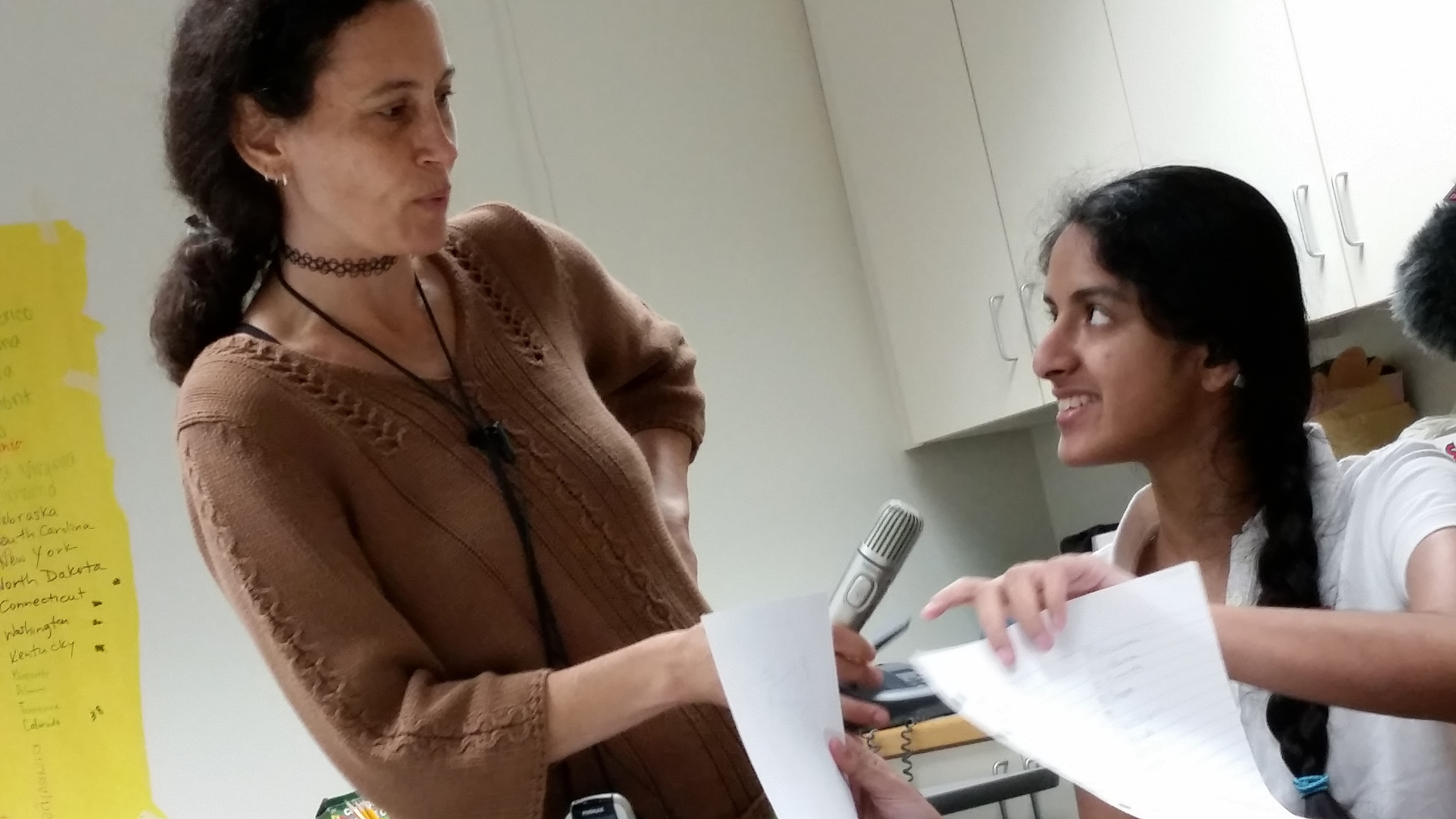

It’s summer at CREC Soundbridge, a school for deaf and hard-of-hearing students in Wethersfield that focuses on the oral method.

There are four students and two adults in one of the classrooms. One of the adults is a teacher of the hearing impaired, and the other is going to school for that job.

The students are middle-school aged, and they’re learning about the 50 states. It’s a subject usually discussed in elementary school, but these students are far behind.

As they talk to each other about the states, they speak into a microphone that broadcasts their words through an FM signal directly to the their cochlear implants and hearing aids. There’s only one microphone, so they have to share.

Elizabeth Cole, Soundbridge’s director at the time, asked one student to talk about the state he picked.

“Why don’t you tell them what you presented today, you presented a full state today,” Cole said to the student. “Do you remember what state you presented?”

The student answers, but his speech is difficult to understand. Cole repeats his answer.

“New Jersey,” Cole said. “What about New Jersey was special to you?”

The student goes on to explain. The other students fidget as they listen — his speech is muffled. He talks for about a minute before Cole jumps in.

“Atlantic City, that’s a hard one,” she said.

Cole and the teachers do a lot of clarifying. They make sure each student is speaking into the microphone. They are always making sure the students hear what was said.

In a later interview, Cole pointed out that these students have additional disabilities that make it hard for them to acquire spoken language. She didn’t discuss specifics for the children in this classroom, but she said all 28 students in summer school this particular year have additional challenges.

“The reality is, too, that the kids who struggle the most with spoken language, are kids who often have come very late to an auditory option,” Cole said.

Twenty-two of them didn’t have access to sound until they were three years old or older, she said. It’s unclear, however, what their exposure to any language has been, including speaking or signing.

As far as their lack of access to sound — that can happen for a variety of reasons, Cole said. Parents who speak English as a second language, for example, might not understand the infant auditory screening process after birth. Or some parents might hope their child will pick-up spoken language eventually. Some might simply refuse to believe their child is deaf.

But it’s that gray area that exists between language choice and language acquisition that has had researchers debating for more than a century.

It’s that gray area that exists between language choice and language acquisition that has had researchers debating for more than a century.

“It’s not a simple thing, by any means,” Cole said. “Sometimes one of the issues that you’re dealing with is: How long do you continue to try to do something — try to provide auditory access — and when do you make the decision that it’s time to change?”

Parents can also make this process difficult, especially if they’re convinced that their child should speak and hear.

“Sometimes they are extremely strong about how they don’t care if the kid is really delayed,” Cole said. “He’s making progress, and they want him to stay in a spoken language instructional mode.”

Jeff Bravin knows this scenario well. Nearly two-thirds of his high school students come to the American School for the Deaf after years of failing in traditional schools, which mostly focus on speaking and listening.

“It’s really sad, it’s heartbreaking, actually,” Bravin said. When students come to his school and are behind academically, teachers focus on job training. “Students who come here, if they have no language, no real solid foundation… you teach them life skills.”

Early speech delays are among the most common struggles faced by all children, but for deaf students, a speech or language delay can be devastating. If the delay is prolonged, it can lead to language deprivation, which often causes mental health difficulties, lower quality of life and additional trauma. Without language, learning anything becomes almost impossible, according to a paper in the Harm Reduction Journal.

Researchers suggest that language deprivation could be a key contributing factor to another startling detail — between 30 and 40 percent of all deaf and hard of hearing children have additional disabilities, such as autism, a learning disability, or ADHD, according to research done by Gallaudet University. Compare that to hearing children, where the prevalence rate is about 12 to 15 percent.

Whether language is spoken or signed, children need language to ensure their brains develop appropriately, and so they can learn other things. Technological innovations, like the cochlear implant, have been heralded by oralists as a key part of the solution to help avoid language deprivation for deaf children. But for those who want their children to sign, there hasn’t been a comparable solution.

But that could be changing. Petitto and her team at Gallaudet University have developed a robot that uses artificial intelligence, thermal imaging, and a computer screen with a human-like figure to teach sign language to infants. The device is activated when it senses that the child is ready to learn through eye-tracking and imaging.

“There are a vast number of children throughout the nation and world who suffer from the devastating effects of minimal or delayed language exposure,” Petitto wrote. “This is especially challenging for… young deaf infants who initially have little (or no) exposure to a fully accessible natural signed language.”

This raises the question of access — technology isn’t cheap, especially when it’s new. And Petitto’s tech involves multiple parts and different software components, making it quite complex. On the other hand, cochlear implants are also complex, expensive and imperfect.

Additionally, cochlear implants sometimes fail — between three and five percent of implanted children undergo reimplantation, most often the result of device failure, according to a study published in The Laryngoscope journal. A Gallaudet survey found that about 10-percent of those who had gotten an implant were no longer using them. However, success rates do seem to be increasing as technology advances and surgery techniques improve.

Technology has been a source of both inspiration and consternation. Soon after cochlear implants were approved for use in children, in 2000, research into deaf education matters plummeted, one study found. Fears among some people got so bad that they attempted to define deafness as an ethnicity to enable signing Deaf people with the same civil right protections afforded to ethnic groups. Others sought to establish a constitutional right to language to protect signing.

In many ways, however, much of the controversy described in this story are problems of privilege. For the majority of deaf people around the world, technology is the last thing available to them, as is learning how to sign.

Photo: Cloe Poisson for Connecticut Public Radio

When Choice Could Be a Luxury

Many families don’t have the time or money it takes to either learn ASL fluently or pay for cochlear implants and related speech services.

“If a family is less likely to get a cochlear implant, it’s because they’re poor,” said Geers, the developmental psychologist. “There is a bias in our system against poor people getting these high-end devices.”

Connecticut has been aware of the accessibility problem. It’s one of 43 states that mandates newborn hearing tests soon after birth. However, even with the screening, many deaf children fall through the cracks in Connecticut, health department data show. Some families decline the hearing test. Some fail to show up for further diagnostic screening. Some parents move out of state. Some parents go through the whole process but never enroll their children in a Birth-to-Three program.

It used to be worse. Doctors used to tell families to wait a year or more before screening — if they were screened at all. Deaf children would often not get any language for years. Some would never fully develop language, stifling their cognitive development.

This is still a problem for some kids in the U.S., especially the poor, and a big problem for many deaf children around the globe. Because so many deaf children go uneducated, most of the world’s adult deaf population lacks any structured language — visual or oral. The World Federation of the Deaf estimated that 80 percent of the world’s deaf population — some 56 million people — has no formal access to education or language.

Because so many deaf children go uneducated, most of the world’s adult deaf population lacks any structured language — visual or oral.

Otherwise intelligent people have fallen behind, or worse, solely because they weren’t able to learn a language, which is the foundation of all other learning.

Most deaf people in the world are referred to as “homesigners” — people who communicate using a type of invented language, or idioglossia (think of Jodie Foster’s character in the 1994 film, “Nell”). Homesigners are deaf people who grow up in a hearing family and have no exposure to any formal language. Most of them live in rural areas, far from access to any type of service.

Deanna Gagne, a researcher who has studied homesigners in Nicaragua and who grew up with deaf parents, said little is known about this large and dispersed community.

“They never have an opportunity to learn a language, nor do they have the opportunity to create a community of language users,” Gagne said. “So each home signer has their own way of doing things.”

When homesigners gather in groups for long periods of time? That’s when things can get interesting. It’s how Nicaraguan Sign Language emerged barely 40 years ago. A new special education program in Managua had enrolled about 50 homesigning deaf children. For the first time in their lives, these students had found a community, and they naturally began signing to each other.

Since then, a small team of language researchers, including UConn’s Marie Coppola, have been studying the evolution of Nicaraguan Sign Language and its impact on homesigners. But when researchers first started to document the people, they encountered significant challenges that were difficult to anticipate.

“Many, many deaf people didn’t know how old they were, didn’t know what year they were born, weren’t sure what year they started school,” Coppola said. “There were a lot of biographical gaps in their knowledge, and that’s mostly because they don’t share a language with their parents.”

And that’s the heart of this debate: parents want to share a language with their children. In places like Nicaragua, those desires are the same, but access to services is often non-existent.

That’s not to say all is lost.

Deanna Gagne tells a story about a woman who lived deep in Nicaragua’s jungled hills. She would walk with her deaf daughter for three hours to school in the town of El Sauce every Saturday, so her child could learn sign language. Then they’d walk three hours back home, up a steep road that wound into the dense forest of the Segovia Mountains. The mother eventually learned her toddler was also deaf. With no access to hearing aids, cochlear implants, or even speech therapy, her options were limited.

As the woman shared her story, Gagne could sense the mother’s hopelessness. So Gagne showed her a photo of herself and her husband, Kurt.

“I said, ‘This is my husband. He is deaf. He has gone to college. He has a job. We are raising children’,” Gagne said. “It was as if I had described an alien planet to her. She had never thought that a deaf person could do so much, and those are pretty normal things for us.”

The photo offered a glimpse of another life. Of possibility. The woman asked if she could keep the photo.

That interaction has stayed with Gagne. She herself would eventually give birth to a deaf child and face the same reality as this Nicaraguan mother. Except in Gagne’s case, the struggle wouldn’t be about access to language. It would be about something else.

Photo: Ryan Caron King, Connecticut Public Radio

Finding Home

Back home in Connecticut, Deanna and her husband, Kurt, are raising three children — Leo and Lewis are hearing, and Logan, a toddler, is deaf. The boys prefer to talk, even though they also sign. Lewis even claims an ability to speak an avian language.

“When I was waiting for the bus, I talked to a bird,” he said, Deanna laughing behind him. When asked how the bird responded, Lewis clucked a few times.

“See, once you know one [other language], the rest are a breeze,” Deanna joked.

Deanna grew up with deaf parents, and learned ASL very young. She actually learned it at a younger age than her husband. Kurt’s parents could hear, and didn’t realize he was profoundly deaf until he was 18-months old. A neighbor had come over and was playing with Kurt on the floor. The neighbor clapped and made other sounds, but the toddler didn’t respond.

“It never occurred to me to even do that,” said Kurt’s mother, Elaine Gueutal, whose first interaction with a deaf person happened when her son was born. After noticing that Kurt didn’t respond to sound, their neighbor turned to his wife. Elaine remembers what he said next.

“I think there’s something wrong here.”

That reaction remains common today. But Deanna and Kurt felt something else when Logan was born — something was wrong, but it wasn’t with Logan.

“For me, her deafness is not a barrier for her,” Deanna said. “What’s a barrier for her are people. And the people around us, and the way that people would view her, is the part that… that I grieved over.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Rachel Posner.

“I’m a mom first, a deaf woman second,” she said. “When I found out my babies were deaf, I wasn’t like, ‘Woo hoo, let’s break out the champagne.’ My heart broke. And it didn’t break because my kids were deaf. It broke because the world is an ugly place.”

On the one hand, the women’s children will share a language connection with people in their family. But they’ll also spend a lot of time in the hearing world, which tells them in different ways that their deafness is something that should be cured and not celebrated.

Perhaps it’s both, or maybe it’s neither. One thing’s for certain, at least in the Gagne household. Logan won’t be getting cochlear implants. At least not until she’s old enough to decide for herself.

Download the transcript of the “Making Sense” special report on Connecticut Public Radio:

Corrections: An earlier version of this incorrectly said that Henry Posner used a cochlear implant; he uses a hearing aid. The story has also been updated to include the correct spelling of the surname of Kurt Gagne’s mother; her name is Elaine Gueutal, not Guittal. And an earlier photo caption misidentified a school West Hartford. It is the American School for the Deaf, not the School of the Deaf.